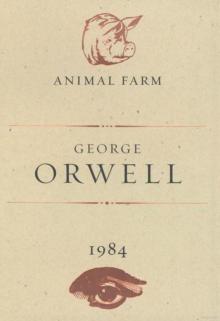

Animal Farm & 1984

Animal Farm & 1984 Homage to Catalonia

Homage to Catalonia Decline of the English Murder

Decline of the English Murder Coming Up for Air

Coming Up for Air Keep the Aspidistra Flying

Keep the Aspidistra Flying Facing Unpleasant Facts: Narrative Essays

Facing Unpleasant Facts: Narrative Essays The Complete Novels of George Orwell

The Complete Novels of George Orwell All Art Is Propaganda: Critical Essays

All Art Is Propaganda: Critical Essays Down and Out in Paris and London

Down and Out in Paris and London Why I Write

Why I Write Nineteen Eighty-Four

Nineteen Eighty-Four A Life in Letters

A Life in Letters Essays

Essays A Clergyman's Daughter

A Clergyman's Daughter Fifty Orwell Essays

Fifty Orwell Essays Burmese Days

Burmese Days Shooting an Elephant

Shooting an Elephant 1984 (Penguin)

1984 (Penguin) A Collection of Essays

A Collection of Essays 1984

1984 The Complete Novels

The Complete Novels All Art Is Propaganda

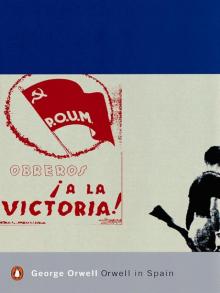

All Art Is Propaganda Orwell in Spain

Orwell in Spain Animal Farm: A Fairy Story

Animal Farm: A Fairy Story Animal Farm and 1984

Animal Farm and 1984